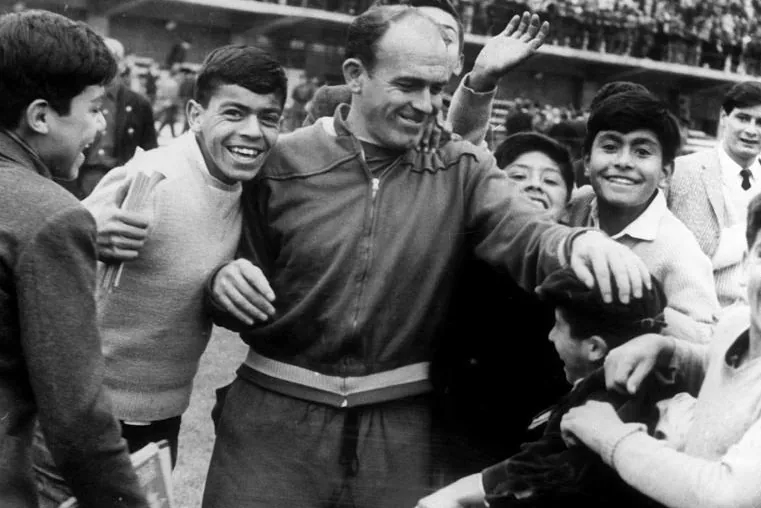

The incredible twists and turns that kept Di Stéfano from ever playing in a World Cup: two nationalities, a disastrous qualification, and a confidential report.

Alfredo Di Stéfano was born in July 1926, so the World Cup's return after the war, Brazil 1950, caught him at the age of 24, in the midst of his rise. In 1947, he had made his debut for Argentina in the South American Championship in Guayaquil, from which he returned as a champion, scoring six goals in six matches. But he didn't go to that World Cup. Argentina didn't register, angry that Brazil had been chosen as the venue for the World Cup's return to South America. Perón , the country's president, declared war on FIFA, and Argentina wouldn't attend either that tournament or the next one. And even if he had gone, he wouldn't have done so with Di Stéfano, who had fled to Colombia to play for Millonarios in a pirate league.

For Switzerland 1954, Argentina also didn't register. Di Stéfano was now at Real Madrid, but hadn't yet become a naturalized citizen. The 1953-1954 season was his first season here, and as a native of a "Hispanic American" country, he would be entitled to dual nationality after two years in Spain. And, according to FIFA rules, he would only be eligible after three. At 28, another World Cup passed him by.

He became a Spanish national in 1957 and made his debut for Spain against the Netherlands on January 30, 1957, alongside Luis Suárez . Spain won 5-1 with three goals from Di Stéfano. A future was opening up for the national team, which had been absent from Switzerland 1954 due to a disastrous elimination against Turkey. For Sweden 1958, we faced a three-way league with Switzerland and Scotland. There was great optimism: Spain had debuted a sensational forward line against the Netherlands: Miguel, Kubala, Di Stéfano, Luis Suárez, and Gento . Miguel, the least remembered, was an excellent Canarian winger from Atlético Madrid. That attack was well supported by solid midfield and defensive players, and two great goalkeepers, Ramallets and Carmelo . We couldn't fail.

And yet the first two games were enough to leave us feeling devastated.

We started on March 10, 1957, against Switzerland at the Bernabéu. Coach Meana repeated the forward line that had thrashed the Netherlands. The stadium was packed, as expected, but it didn't feature the same performance as the Netherlands had done. Instead, it was a confusing match that ended in a difficult 2-2 draw. Switzerland, the inventors of the lock, used it deliberately, and our attack was poorly executed. Since Di Stéfano and Kubala tended to drop back, Meana brought in Luis Suárez, a creative midfielder, as a striker amid the tangle of Swiss defenders, where he was poorly managed. We also neglected our counterattacks, and a certain Hügi II scored two goals against us.

The second match was a visit to Scotland, after a friendly in Brussels where we recovered our morale by beating Belgium 5-1. In Kubala's place, Mateos played, a very mobile, elusive midfielder with a nose for goal. It worked. But in Glasgow, we reverted to the Kubala-Di Stéfano formula and lost 4-2, on a soft pitch and in the rain. It would be pointless to win 4-1 against Scotland and 4-1 against Switzerland. The Scots won well in both matches against the Swiss to eliminate us. These were Di Stéfano's best years. A few days after the Scotland match, Madrid won its second European Cup. And shortly before the start of Sweden 1958, it won its third. It would also win the next two, always with Di Stéfano as the team's 'alma mater'. He was 32 years old, but he was at his peak.

The fourth and final opportunity was Chile 1962. Di Stéfano was approaching 36, had lost momentum, but was still current. His Madrid team won the League and the Cup, and reached the European Cup final, losing 5-3 to Benfica. This serves as a benchmark for the level he still maintained, because he was the soul of the team. Furthermore, Atlético Madrid won the Cup Winners' Cup, and Valencia beat Barça in the Fairs Cup. That was the level of our football: three European championships, four finalists, and two champions. So much was expected of the national team after a long decade of disappointment. Fourth place in Brazil 1950 was already so far away...

The qualifying system was different: two knockout ties. First, Wales: 1-2 at Ninian Park in Cardiff, and 1-1 (in front of 110,000 spectators!) at the Bernabéu. We advanced, but without boasting. The next round was against Morocco, the African Group II champions: 0-1 at the Marcel Cerdan Stadium in Casablanca and 3-2 at the Bernabéu, this time in front of 50,000 spectators.

Pedro Escartín , the national team coach, had announced that he would not continue under any circumstances and handed over the reins to Hernández Coronado , an ingenious man who invented the position of technical secretary at clubs and was renowned for his witty ideas. When he was managing Madrid, he created a different starting eleven for home and away matches, understanding that the demands were different. The experiment lasted until Bernabéu got fed up. He was also the one who introduced shirt numbers in Spain and peppered his career with witty one-liners. He didn't like journalists much. He wrote: "To write about football for a newspaper, you must meet two requirements: be a friend of the editor and be good for nothing else."

During the substitution, a very notable incident occurred. Pedro Escartín left a report at the Federation on the worth and conditions of the players he considered eligible. MARCA got hold of a copy, published it in full, and all hell broke loose. He said of one goalkeeper ( Araquistáin ) that he would be the best if his nerves didn't get to him; of another ( Vicente ) that he would be the best if he were truly recovered from his injury; of another ( Carmelo ), that he was worse than the previous two and less courageous, but more experienced. He considered one defender to be tough, another to be slow, one midfielder to be good with his head but bad with his foot, and another to be blind to the pass.

It was a well-intentioned report, and as far as I could see from those players, correct, but full of morbid curiosity for barroom conversation. Only Luis Suárez passed without objection. Particularly controversial was the joint assessment of left wingers Gento and Collar , whose merits the Real Madrid and Atlético fans argued heatedly about every day. Escartín's opinion was this: "Collar is better this season, and with a lot of desire. In Chamartín, against Morocco, he was crushed by the passion of the crowd. Gento has lost some of his speed, which is his best weapon, and I have the impression that this kid isn't living a good life, and I'm sorry because he's excellent. Both will go out and play with enthusiasm, but I insist that Collar has a more consistent record in my books." What a mess!

But if I bring up this anecdote, it's to lead into my judgment of Di Stéfano: "If this player, who is going to be devastated at the end of the season, makes good use of the five weeks before the World Cup, he's still indispensable and the best of all, by a long shot. He can't play three games in eight days. I'm happy with that. But two, yes. He's the man who feels the most responsibility, or one of the most. And he gives everything he can. He's lost speed, it's logical, but his intuition in front of goal, the way he links and performs, make him indisputable. A man who initially was aloof in character, when he trains he really does it. He pays attention to everything and his morale must be taken care of."

That was, indeed, the Di Stéfano of those days, and as such he was included in the initial list of 29 players that the controversial Helenio Herrera , formerly of Barça and then at Inter, from which he had brought Luis Suárez, was going to work. At the time, there was a national team manager who chose the players and made the lineup, and a coach who oversaw their physical, technical, and tactical preparation. The pairing of such extreme characters smelled fishy from the start, and was even given the name of a chemical formula: H3C, for Helenio Herrera and Hernández Coronado. Helenio and Di Stéfano did not get along, due to untimely statements by the coach when he was at Barça, in which he called the player old.

Six preparation matches were scheduled between April 29 and May 17, at the Metropolitano, El Sardinero, San Mamés, San Mamés again, and Atocha, after which the seven were discarded, and the return to the Metropolitano. The sparring partners were European clubs: Saarbrücken, Stade Reims twice, Osnabrück twice, and Bayern.

On May 13, at Atocha against Osnabrük, Di Stéfano felt pain in his thigh in the 65th minute and withdrew. There were 18 days left until Spain's first match in Chile, and the situation didn't seem serious enough to rule him out, so he was announced on the final 22-man squad. He didn't play in the last match, on May 17 against Bayern Munich. On May 20, the day of the departure, Helenio Herrera had the idea of doing a very tough training session at five in the afternoon in preparation for the long journey, which would begin that night at one in the morning. The crowd was applauding the intensity of the exercises when Di Stéfano withdrew after 25 minutes, clutching his thigh after being hit by a whiplash.

He spoke with Dr. Cabot , gesticulated a lot, they jogged together along the stretch, and then stopped. Hernández Coronado approached and Di Stéfano told him: "I can't go, I'm not fit. Find someone else." Cabot insisted: "I promise to cure you in 10 days." While HH watched from the field, where the others continued working, Di Stéfano insisted: "I can't handle such intense training; find someone else." But it was unthinkable, and the doctor's optimism prevailed: "It's nothing. A simple consequence of the intensive treatment he's been undergoing. A minor muscle contraction."

At midnight, in Barajas, Di Stéfano said glumly, "I think I'm going as a tourist." Cabot countered: "I'll say he'll be better in a few days. We have to get him out of this idea that he won't be able to play." The trip was excruciating: 18 hours, with stops in Rio, Montevideo, and Buenos Aires. At night, in the seats for three, the arms were raised and there slept the "most important." At the feet, the next most important. And the rest, in the aisle. That's how footballers traveled back then.

The day before the first match, against Czechoslovakia, on May 31, there was still talk of him being a doubt, but it wasn't to be. We lost 1-0. On June 3, Mexico's match is scheduled for June. It's said he could be, but it's better to save him for Brazil. We won 1-0. Let's see if he could play against Brazil this time around, with Di Stéfano... But he couldn't play against Brazil either. Dr. Cabot's witchcraft predictions were all smoke and mirrors. We lost 2-1, and that was it. Di Stéfano, as feared, traveled as a tourist. And he returned in a foul mood. Helenio Herrera took it out on the four fatties of the expedition: Puskas, Eulogio Martínez, Santamaría , and Di Stéfano, to whom he gave an apple as a dinner, and posted a guard in the hotel kitchen to keep them out. Di Stéfano lost four kilos and began to suffer lifelong back problems, which he always blamed on HH for insisting on reducing his weight to the level he'd always played at. He returned without a World Cup and with a problem that plagued him forever.

elmundo